I love watches, mechanical ones, and all the clockwork mechanisms, even if it is a wind-up old circus monkey toy. There is something so special in these ingenious mechanisms; there is some sort of magic.

In fact, it's not only me that is affected by the clockwork and, well, "mechanology.' It influenced whole schools" of thought and even cultures.

In the Victorian era, many people viewed the universe as a vast, perfectly designed machine. This belief wasn't just an abstract idea; it was tied to their growing confidence in science, reason, and human understanding.

Astronomic observations at the time confirmed the idea: planets and celestial objects moved in a highly predictable, clockwork fashion. That is until the discovery of Mercury; that one ruined the game; it not only wiped the pieces off the board, it broke the whole board.

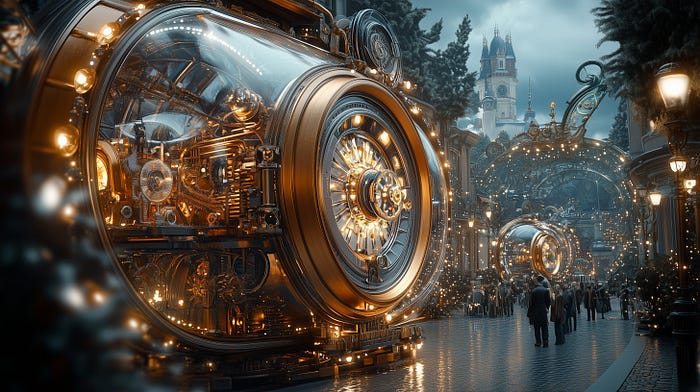

But, to Victorians, the universe was like a clock — intricate, precise, and predictable. By understanding its parts, they believed, you could understand the whole.

Why a Clockwork Universe?

The 19th century was a time of rapid scientific progress. Isaac Newton's laws of motion and universal gravitation had laid the groundwork for seeing the universe as governed by fixed, knowable rules. Victorians admired this order. The Industrial Revolution was happening and penetrating all levels of society; they saw machines performing precise, reliable work.

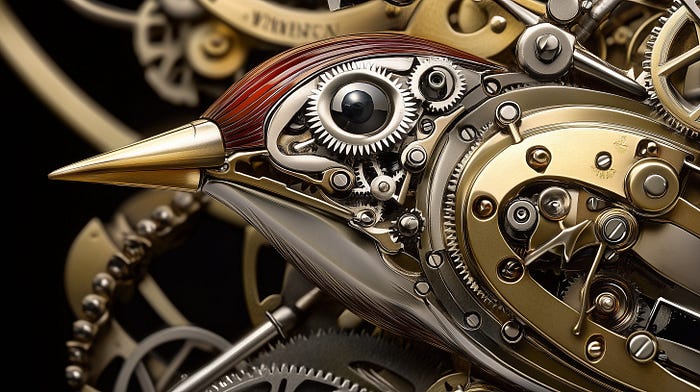

Those precisely machined, intricately meshing gears and cogs seemed to be an embodiment of universal order.

It seemed natural to imagine the cosmos working the same way — gears turning in complex, ticking harmony, guided by natural laws.

This view wasn't just a metaphor; it shaped how Victorians thought about life, nature, and even morality. If the universe was mechanical and predictable, where everything had its place and purpose.

People believed they could unlock the mysteries of existence by observing and reasoning, just as engineers could understand and repair machines.

Science and Certainty

Victorian scientists and thinkers were optimistic. They believed the universe was not random or chaotic but governed by laws humans could discover, measure, and quantify. Astronomy, physics, and biology seemed to support this idea.

For instance, Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species (1859) described evolution as a process driven by natural laws, like the survival of the fittest. It gave order to life itself, fitting neatly into the mechanistic worldview.

Even the study of society followed this trend. Thinkers like Herbert Spencer tried to apply the idea of natural mechanistic laws to human progress. They believed societies evolved just as species did, moving toward higher stages of development, and engaged in mechanistic, gear-like interactions.

The Appeal of Predictability

The clockwork universe was comforting. It suggested that the world was stable, unchangeable, and understandable. In a time of rapid change — industrial revolutions, urbanization, and scientific breakthroughs — this sense of order helped people make sense of their lives. If everything followed a rule, then nothing was truly unknown or unknowable.

This predictability also supported religious ideas. Many Victorians believed God was the "watchmaker" who had designed the universe. By studying the natural world, they felt they were uncovering the work of a divine creator.

The Limits of the Mechanistic View

But this belief had its limits. By the late Victorian period, cracks began to appear in the clockwork metaphor. Discoveries in physics, such as the study of heat and energy, showed that the universe wasn't as perfectly efficient as a clock. The laws of thermodynamics, particularly the concept of entropy, showed that energy dissipates over time, systems become less orderly, and inevitably change. This idea conflicted with the neat, eternal precision of the mechanistic worldview.

Moreover, the rise of fields like chaos theory and quantum mechanics (though fully developed later) hinted that not everything could be predicted or understood with simple rules. Human behavior, complex systems, emergence, and the subatomic world resisted the tidy framework of Victorian mechanics.

Legacy of the Clockwork Universe

Even as new ideas emerged, the Victorian belief in a mechanistic universe left a lasting impact. It shaped how we think about science, progress, and our ability to understand the world. While we now know the universe is more complex than a clock, the Victorian age gave us a powerful legacy: the idea that the world is knowable and that through careful study, we can uncover its secrets.

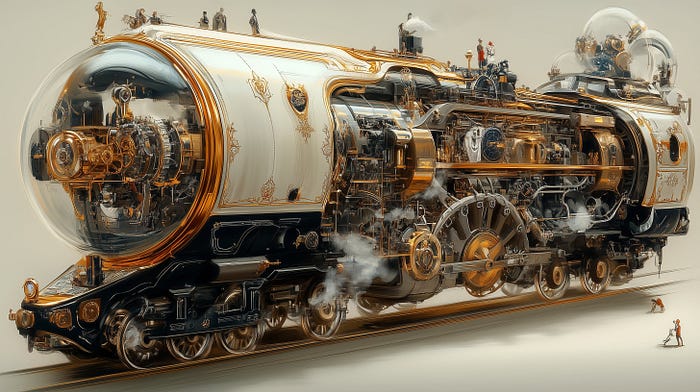

Victorians gave us the idea of the possibility to measure time extremely accurately in any conditions and hence, navigate the world with high precision. They created a machine of extraordinary beauty, not in its external design, but in its intrinsically beautifully crafted components: levers and gears, carved-out retaining plates, and cast-in-graceful-shaped frameworks and support elements.

They were pieces of artwork, just as much as of ingenuity. Even I, while studying engineering, learned an old adage: if your mechanical solution does not look beautiful, it probably is a bad solution.

Victorian mechanology and clockworks and steam machines gave birth to a whole new rebellious artwork — steampunk too. And while it is all cogs, gears, pipes, and steam, this art form rebels against human beings being a part of the machine, a small cog in a system, something described by manual and driven by instructions.

I love it all. I love the history of it; I love the art forms it gave, and I love to play with cogs and wheels in my art too.

But when it comes to Midjourney, there are some problems involved. Midjourney is neither an engineer nor a mathematician and cannot count very well.

So if you expect images of perfectly meshing gears and evenly spaced cogwheel teeth, that's not going to happen.

But we are creating art, not an engineering diagram, so this could be forgiven.

And like Victorians, we can create anything we want with clockwork and mechanolgy, the whole universe, if that's what you want.

"Clockwork fantasy, gears and cogs and intricate mechanisms creating a mechanistic universe, planets, stars, and automatons made of cogs, wheels, rivets, and screws, and engraved brass plates — ar 16:9 — personalize b7emh7c ged4sfw — stylize 1000 — v 6.1"

Other variations of the prompts you will find underneath example images. I created just a few of them, but possibilities are truly endless: automatons and clockwork animals, appliances and secret devices, and, of course, time machines of all sorts.

I had fun; I hope you will have fun too and learn something about how Midjourney and your mind work on the way. And I wish you good luck!

Aivaras Grauzinis